On the clock: Escaping VMware Workstation at Pwn2Own Berlin 2025

Looking to improve your skills? Discover our trainings sessions! Learn more.

Introduction

At Pwn2Own Berlin 2025, we successfully exploited VMware Workstation using a single Heap-Overflow vulnerability in the PVSCSI controller implementation. While we were initially confident in the bug's potential, reality soon hit hard as we confronted the latest Windows 11 Low Fragmentation Heap (LFH) mitigations.

This post details our journey from discovery to exploitation. We start by analyzing the PVSCSI vulnerability and the specific challenges posed by the LFH environment. We then describe a peculiar LFH state that enables deterministic behavior, alongside the two key objects used for spraying and corruption. Building on this setup, we demonstrate how to leverage the vulnerability to craft powerful memory manipulation primitives, ultimately achieving arbitrary Read, Write, and Code Execution.

Finally, we reveal how—just two days before the contest—we exploited a timing side-channel within the LFH to fully defeat its randomization, ensuring a first-try success during the live demonstration.

The PVSCSI Bug

vmware-vmxlinux/drivers/scsi/vmw_pvscsi.cPVSCSISGElement

struct PVSCSISGElement {

u64 addr;

u32 length;

u32 flags;

} __packed;

bool __fastcall PVSCSI_FillSGI(pvscsi_vmx *pvscsi_vmx, ScsiCmd *scsi_cmd, sgi *sgi)

{

// [...]

while ( 1 )

{

next_i = i + 1;

if ( 0x10 * (unsigned __int64)(i + 1) > leftInPage )

{

Log("PVSCSI: Invalid s/g segment. Segment crosses a page boundary.\n");

goto return_invalid;

}

idx = i;

pInPage = &page[idx];

if ( (page[idx].flags & 1) == 0 )

{

seg_len = page[idx].length;

if ( sg_table_len_1 < seg_len )

seg_len = sg_table_len_1;

seg_count = sgi_1->seg_count;

if ( seg_count > 0x1FF )

{

v13 = page;

pEntries = (SGI_Entry *)UtilSafeRealloc1(

sgi_2->entries_buffer,

0x4000uLL,

0xFFFFFFFF,

"bora/devices/pvscsi/pvscsi.c",

0xC5A);

page = v13;

sgi_1 = sgi_2;

sgi_2->entries_buffer = pEntries;

sgi_2->pEntries = pEntries;

seg_count = sgi_2->seg_count;

}

else

{

pEntries = sgi_1->pEntries;

}

seg_idx = (int)seg_count;

pEntries[seg_idx].addr = pInPage->addr;

pEntries[seg_idx].entry_size = seg_len;

sg_table_len_1 -= seg_len;

sgi_1->seg_count = seg_count + 1;

goto loop_over;

}

// [...]

}

UtilsSafeRealloc1()

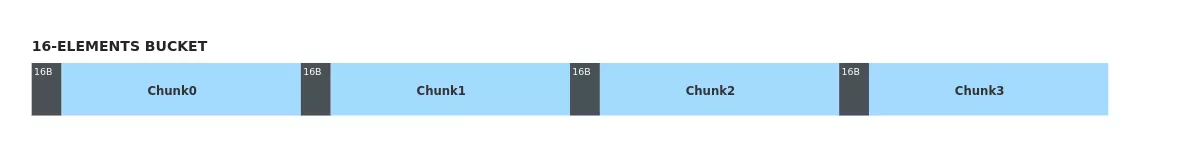

addrlengthA Heap of Trouble

p2 = malloc(0x4000); // Allocate the new chunk

memcpy(p2, p1, 0x4000);

free(p1); // Free the current chunk

memcpy(p2+0x4000, elem, 16); // Write 16 bytes past the end, corrupting the new chunk's metadata

A Tale of Two Objects

Shaders

URBs

Offset +0x00 +0x04 +0x08 +0x0C

+---------------------------------------------------------------+

0x00 | refcount | urb_datalen | size | actual_len |

+---------------------------------------------------------------+

0x10 | stream | endpt | pipe |

+---------------------------------------------------------------+

0x20 | pipe_urb_queue_next | pipe_urb_queue_prev |

+----------------------------///////----------------------------+

0x70 | data_ptr | unk |

+---------------------------------------------------------------+

0x80 | pDataCur | pad |

+---------------------------------------------------------------+

| Variable-size |

0x90 | |

| User Data |

+---------------------------------------------------------------+

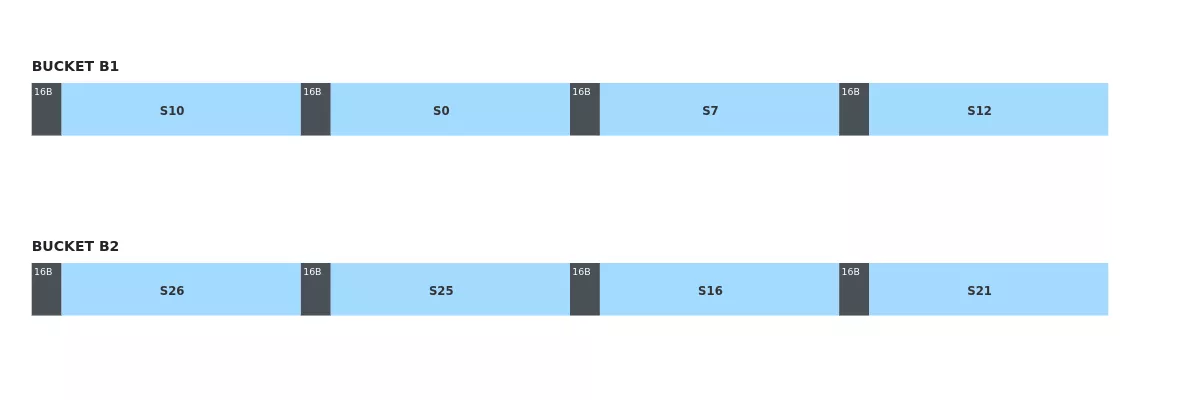

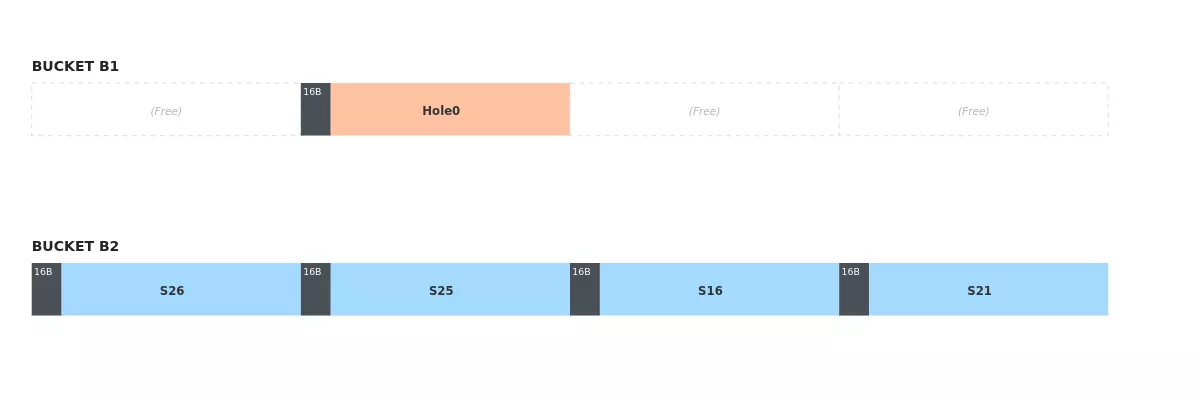

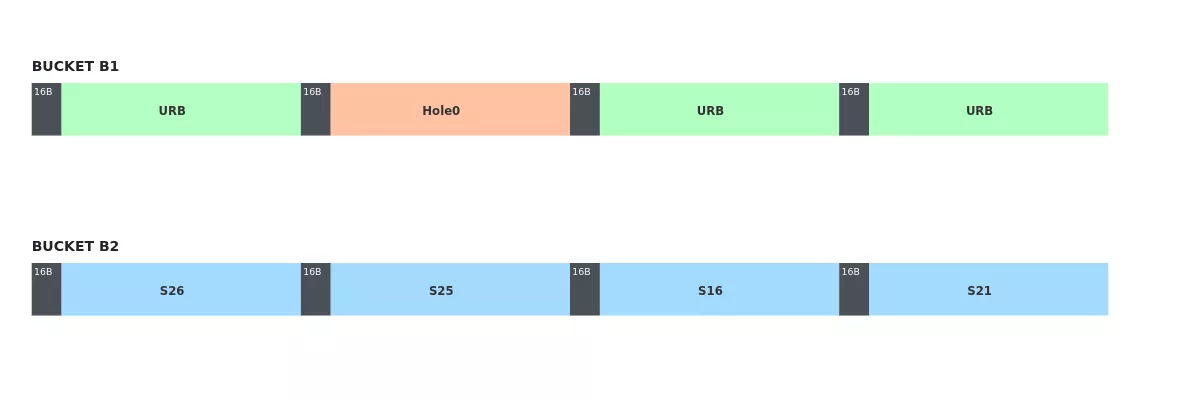

Winning a Ping-Pong Game

The Reap Oracle

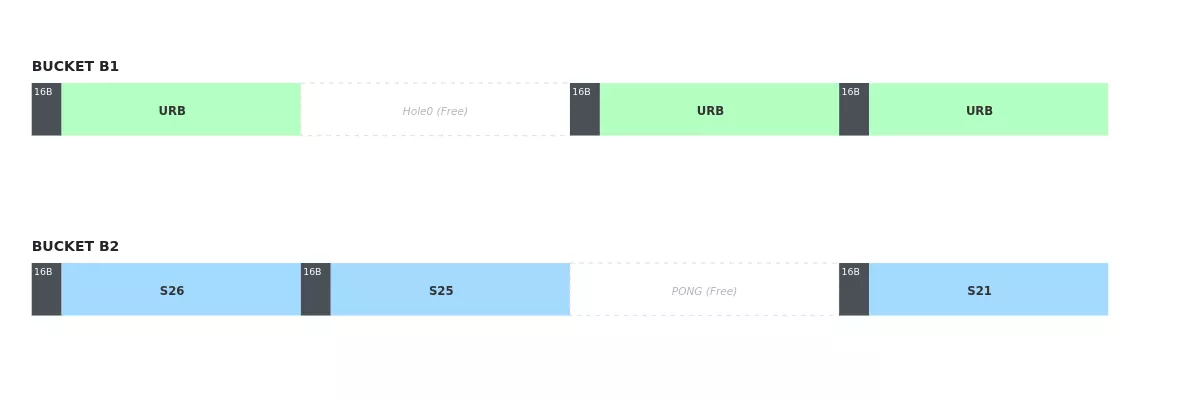

To implement the rest of our primitives, we needed four contiguous chunks in a known order in B1. This is where the Reap Oracle comes into play. As previously mentioned, allocated URBs are stored in a FIFO queue. By repeatedly calling the UHCI controller's reap method, we can retrieve the content of the next URB in the queue and free it. This allows us to detect which URB was corrupted.

The 16-byte overwrite affects the following four fields of the URB structure:

struct Urb {

int refcount;

uint32_t urb_datalen;

uint32_t size;

uint32_t actual_len;

[...]

}

The critical field here is actual_len. Recall that for the 16-byte overflow, we control the first 12 bytes, but the last 4 bytes are always forced to zero. Consequently, the overflow invariably sets actual_len to zero. This corruption acts as a marker, allowing us to identify the affected URB.

The Reap Oracle Strategy:

- Allocation: We allocate 15 URBs to fill the B1 bucket.

- Corruption: We trigger the vulnerability (Ping-Pong) to zero out the

actual_lenfield of the URB located immediately after Hole0. Then, we allocate two placeholder shaders to reuse Hole0 and PONG. - Inspection & Replacement: We iterate through the URB queue. For each URB, we

reapit and check its length. We immediately allocate a placeholder shader in its place. - Identification: When we retrieve a URB with a modified

actual_len, we know that the shader we just allocated to replace it resides in the slot following Hole0. We label this new slot Hole1.

We repeat the process to locate Hole2 and Hole3. For each iteration, we free the non-essential placeholders (keeping Hole0, Hole1, etc.), refill the bucket with URBs, and use the previous Hole as the PING buffer. Once the heap is prepared, we re-execute the corruption and identification steps to pinpoint the next contiguous slot. Ultimately, we obtain a sequence of four contiguous chunks (Hole0–Hole3), currently occupied by shaders, which can then be freed to enforce adjacency for subsequent allocations.

Coalescing Is All You Need

// [...]

res = ((__int64 (__fastcall *)(pvscsi_vmx *, ScsiCmd *, sgi *))scsi->pvscsi->fillSGI)(// PVSCSI_FillSGI

scsi->pvscsi,

scsi_cmd,

&scsi_cmd->sgi);

LODWORD(real_seg_count) = 0;

if ( !res )

return 0;

seg_count = (unsigned int)scsi_cmd->sgi.seg_count;

if ( (int)seg_count <= 0 )

{

numBytes_1 = 0LL;

}

else

{

pEntries = scsi_cmd->sgi.pEntries;

numBytes_1 = pEntries->entry_size;

if ( (_DWORD)seg_count != 1 )

{

next_entry = (SGI_Entry *)((char *)pEntries + 0x18);

LODWORD(real_seg_count) = 0;

for ( i = 1LL; i != seg_count; ++i )

{

idx = (int)real_seg_count;

entry_size = pEntries[idx].entry_size;

addr = ADJ(next_entry)->addr;

if ( entry_size + pEntries[idx].addr == addr )

{

pEntries[idx].entry_size = ADJ(next_entry)->entry_size + entry_size;

}

else

{

real_seg_count = (unsigned int)(real_seg_count + 1);

if ( i != real_seg_count )

{

real_seg_idx = (int)real_seg_count;

pEntries[real_seg_idx].addr = addr;

pEntries[real_seg_idx].entry_size = ADJ(next_entry)->entry_size;

}

}

numBytes_1 += ADJ(next_entry++)->entry_size;

}

}

}

// [...]

Entry 1: {.addr = 0x11000, .size = 0x4000}

Entry 2: {.addr = 0x15000, .size = 0x2000}

Entry 3: {.addr = 0x30000, .size = 0x1000}

Entry 1′: {.addr = 0x11000, .size = 0x6000}

Entry 2′: {.addr = 0x30000, .size = 0x1000}

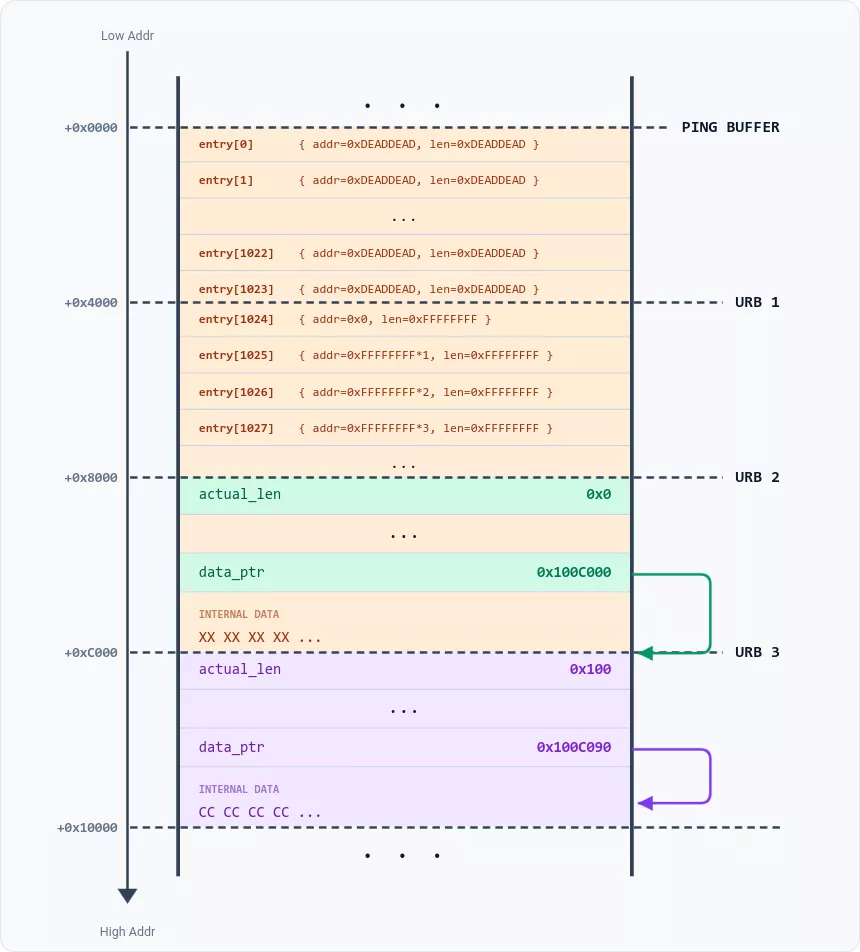

0xFFFFFFFFBuilding a controlled overflow

{.addr=0, .len=0}entry[1023]

entry[2048]entry[1024]

AddrA+LenA==AddrBLenA=0AddrA==AddrB0x4141414141414141 0x42424242424242420x4343434343434343 0x4444444444444444

entry[i] = { .addr = 0x4141414141414141, .size = 0 }

entry[i+1] = { .addr = 0x4141414141414141, .size = 0x4242424242424242 }

Pair 2:

entry[i+2] = { .addr = 0x4343434343434343, .size = 0 }

entry[i+3] = { .addr = 0x4343434343434343, .size = 0x4444444444444444 }

Note that even-indexed entries (with the size set to zero) are written by the heap-overflow, while odd-indexed entries are the ones that were already present in Shader2.

Each pair of entries is merged into a single one due to their matching addresses and the zero size:

entry[i] = { .addr = 0x4141414141414141, .size = 0x4242424242424242 }

entry[i+1] = { .addr = 0x4343434343434343, .size = 0x4444444444444444 }

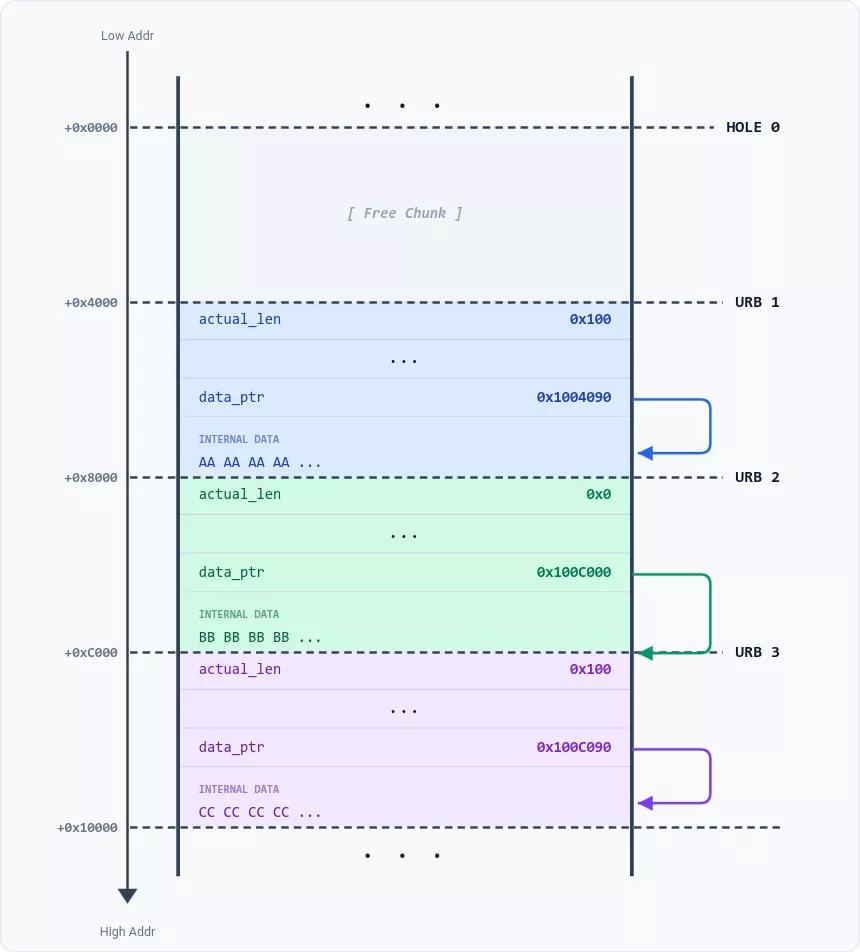

Leaking a URB

actual_lenJiangStep 1: The Setup

actual_len0x0

Step 2: The Overflow

0xFFFFFFFF

Just like in the previous section, we trigger the vulnerability twice in order to overwrite both odd-indexed and even-indexed entries of URB1, and corrupt only half of URB2 intact. We end up with the following state:

Step 3: The Coalescing

0xFFFFFFFF*0x401.actual_len0x400

actual_len0x400

actual_len

Arbitrary Read, Write and Call Primitives

We reuse the memory layout from our leak phase: [Hole0, URB1, URB2, Shader3]

At this stage, URB1 and URB2 have corrupted heap metadata and can no longer be safely freed. However, Shader3 (the former URB3 location) remains uncorrupted and can be freely reallocated at will.

We gain full control over the structure of URB1 by using Shader3 as our source buffer. By placing a forged URB structure inside Shader3 and triggering the "move up" primitive, we shift our data directly into URB1’s memory space, effectively replacing its contents with arbitrary data. Having previously leaked a URB header, we already possess all the pointers necessary to forge a perfectly valid one.

A Persistent Arbitrary URB

To ensure full stability, we aim to create a persistent fake URB that can be controlled through simple heap reallocations, bypassing the need to trigger the vulnerability ever again. The trick is to change the URB1.next pointer to point to Hole0. We also increment the reference count of URB1 to ensure it stays in memory despite its corrupted metadata.

When VMware "reaps" URB1, it sets URB1.next as the new head of the URBs FIFO queue. This effectively places our fake URB in Hole0 at the top of the FIFO. We can now control this fake structure at will by reallocating Hole0 with a new shader whenever needed, removing any further need to trigger the PVSCSI vulnerability.

Read & Write Operations

URB.actual_lenURB.data_ptr

URB.pipe

Call primitive

RCX+0x90

To ensure our exploit is portable across Windows versions, we avoid hardcoded offsets. Instead, we use our read primitive to parse Kernel32 in memory and dynamically resolve the address of WinExec.

The last hurdle is bypassing Control Flow Guard (CFG). We cannot jump directly to WinExec, so we use a CFG-whitelisted gadget within vmware-vmx. This gadget pivots data from RCX+0x100 into a fully controlled argument before jumping to a second arbitrary function pointer, in this case, WinExec("calc.exe").

On the Clock

Two days before the competition—and three days after registering—we finally had a working exploit. The only minor issue was that it relied on the assumption that we knew the initial LFH state—but we didn’t. The number of free LFH chunks was a moving target. Right after booting the guest OS, the value was almost always the same, but as soon as a graphical session was launched, it started changing in unpredictable ways. To make things worse, our various testing setups all had close but distinct initial LFH states. Basically, we needed to pick one number out of 16, knowing only that the odds were somewhat skewed in favor of certain values. At this point, our best strategy was rolling a slightly loaded 16-sided die.

We had previously envisaged a solution based on a simple hypothesis: when a chunk is allocated from the LFH, if all the current buckets are full, the LFH needs to create a new bucket, a process that should take additional time. By allocating multiple 0x4000 buffers and precisely measuring the duration of each allocation, we should be able to detect a slightly longer delay each time a new bucket is created. We hoped this would provide a reliable timing-channel to uncover the initial LFH state.

The catch was that we needed a synchronous allocation primitive. In VMware, almost all allocations are performed asynchronously. For instance, to allocate shaders, we push commands in the SVGA FIFO, which are then processed in the background, leaving us no way to precisely time the allocation.

By chance, VMware exposes one feature that is perfectly synchronous: the backdoor channel. This channel is used to implement VMware Tools features, such as copy-and-paste. It is implemented via "magic" assembly instructions, which return only after the command has been fully processed. Here is an excerpt from Open VM Tools, which provides an open-source implementation of the VMware Tools:

/** VMware backdoor magic instruction */

#define VMW_BACKDOOR "inl %%dx, %%eax"

static inline __attribute__ (( always_inline )) uint32_t

vmware_cmd_guestrpc ( int channel, uint16_t subcommand, uint32_t parameter,

uint16_t *edxhi, uint32_t *ebx ) {

uint32_t discard_a;

uint32_t status;

uint32_t edx;

/* Perform backdoor call */

__asm__ __volatile__ ( VMW_BACKDOOR

: "=a" ( discard_a ), "=b" ( *ebx ),

"=c" ( status ), "=d" ( edx )

: "0" ( VMW_MAGIC ), "1" ( parameter ),

"2" ( VMW_CMD_GUESTRPC | ( subcommand << 16 )),

"3" ( VMW_PORT | ( channel << 16 ) ) );

*edxhi = ( edx >> 16 );

return status;

}

To trigger controlled allocations using the VMware Tools, we leveraged the vmx.capability.unified_loop command [5]. By providing a string argument of 0x4000 bytes, we could force the host to allocate exactly two buffers of that size.

Since a bucket for the 0x4000 size class contains exactly 16 chunks, triggering this command 8 times (for a total of 16 allocations) guaranteed that we would cross a bucket boundary and observe a bucket creation event.

To time the allocations, we relied on the gettimeofday system call. While the timing signal was subtle, it was definitely noticeable. To clean up the noise, we implemented some "poor man's signal processing":

- We triggered the command 8 times to collect a batch of measurements.

- We discarded any batch containing significant outliers (typically much longer measurements caused by host context-switches).

- We summed multiple valid batches to obtain a smoother, more reliable estimation.

When tuned correctly, the results were clear: among the 8 measurements, one was consistently longer, indicating that a new bucket had been created during that specific call. We could then allocate a single 0x4000 buffer and repeat the process to determine precisely which of the two allocations within the command had triggered the new bucket's creation.

This second pass allowed us to deduce the exact LFH offset: if the timing spike appeared at the same index as before, it meant the LFH offset was odd; if the spike shifted to the next index, the offset was even. Any other result was flagged as incoherent—usually due to background heap activity or, more commonly, excessively noisy measurements—meaning we had to restart the process from scratch.

Racing Against Noise

In theory, we could have used a very large number of batches to arbitrarily increase the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). In practice, however, we hit a significant bottleneck in the vmx.capability.unified_loop command: the strings allocated by this command are added to a global list and cannot be freed.

Furthermore, these strings must be unique. This means that every time we issued the command, the host would first compare our string argument against every string already present in the list, only performing a new allocation if it found no match.

This posed a major challenge. Initially, when the list was empty, the string comparison was instantaneous. But after a few hundred allocations, the command had to perform hundreds of comparisons before even reaching the allocation logic. This $O(n)$ search overhead meant that as we were collecting more batches to improve our SNR, the baseline noise and latency were actually increasing.

This created a race against time: every batch of measurements we collected to increase our precision paradoxically raised the noise floor for the next one.

We knew that if the algorithm didn't converge quickly enough, the VM state would become too "polluted" to ever yield a clear reading again. Luckily, after testing and tuning the algorithm on multiple computers, we found a working balance. During the competition, the exploit worked on the first attempt, much to our relief.

Demonstration

Here is a video of the exploit in action:

Conclusion

This research was conducted over three months of evenings and weekends. The first month was dedicated to reverse-engineering VMware and discovering the vulnerability. Convinced that exploitation would be straightforward, we spent the second month procrastinating.

The third month was a reality check. While we developed the drivers necessary to allocate interesting objects, we hit a wall with Windows 11 LFH mitigations, exhausting countless bypass strategies that ultimately failed. Consequently, the core of the exploit—including the leak, the Read/Write/Execute primitives, and the timing-channel—was developed in the final five days leading up to the competition.

While this last-minute sprint ultimately paid off, we strictly advise against replicating our timeline—unless you particularly enjoy sleep deprivation.

References

[1] Saar Amar, Low Fragmentation Heap (LFH) Exploitation - Windows 10 Userspace

[2] Zisis Sialveras, Straight outta VMware: Modern exploitation of the SVGA device for guest-to-host escape exploits

[3] Corentin Bayet, Bruno Pujos, SpeedPwning VMware Workstation: Failing at Pwn2Own, but doing it fast

[4] Yuhao Jiang, Xinlei Ying, URB Excalibur: The New VMware All-Platform VM Escapes

[5] nafod, Pwning VMware, Part 2: ZDI-19-421, a UHCI bug